Anne Gribbons: "The Power of the Seat"

The Power of the Seat

After a lifetime of riding, teaching and judging, I am keenly aware of the fact that a horse cannot perform better than the rider is able to guide him.

Riders who love to ride come in all shapes and sizes. The lucky ones, built with legs to their eyeballs and short upper bodies will usually have the inside track on developing a stable and effective seat. However, there are a number of very successful riders whose conformation is just the opposite and it never got in their way. What is also clear, is that some riders have a natural feel for how to stay balanced within the horse's center of gravity, how to connect with the horse's mouth without interfering with the forward movement and how to influence them with just the right amount of pressure from leg or seat. Those are the dream students who make progress in almost every ride and gladden an instructor's heart.

That kind of student represents about five percent of those you will teach over a long career. The rest will have to learn the hard way, through endless repetitions of corrections of seat and hands until they develop enough "muscle memory” to adapt to the horse without having to think about the process.

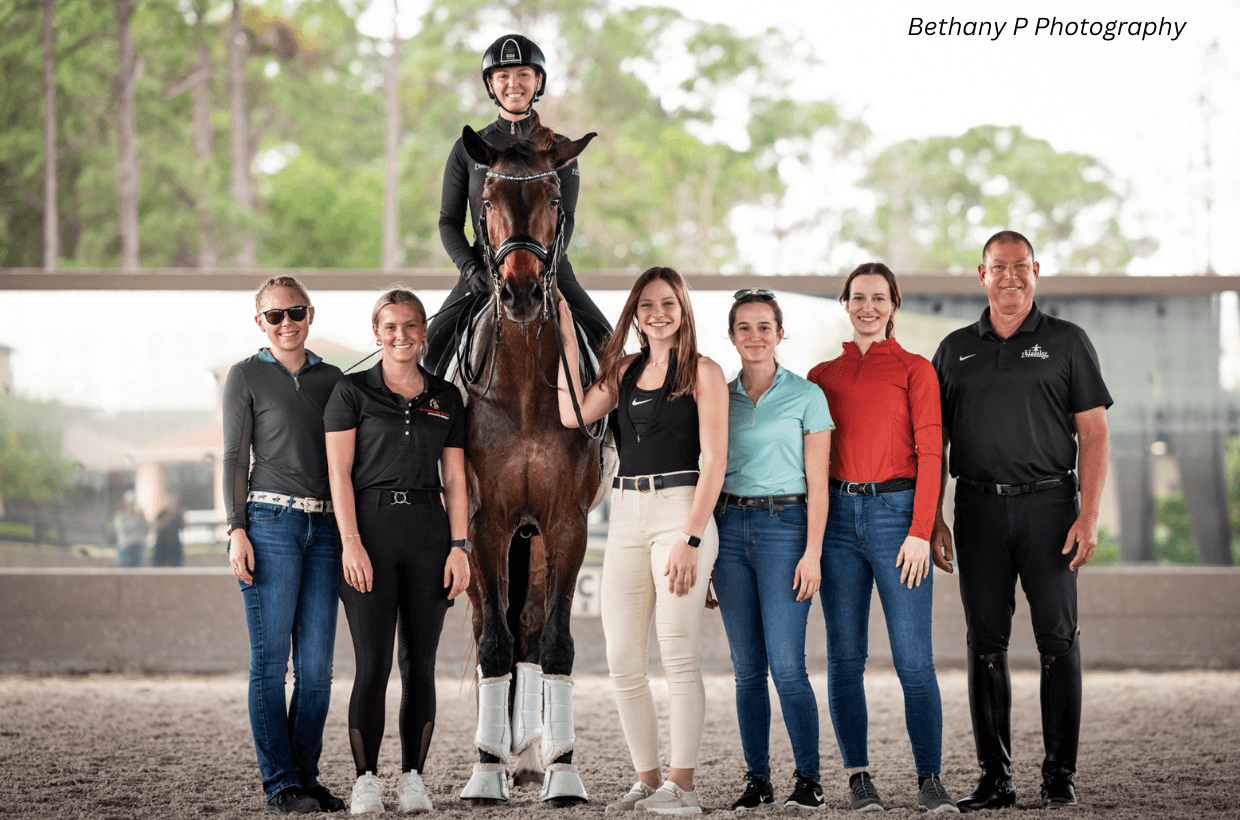

While judging and watching during our busy CDI season, it is rewarding to see how many US riders sit well and guide their horses with suppleness and “feel" as opposed to just a few years ago. It is particularly obvious in our new generation of riders, the “under 35" group, most of whom are home grown and taught by the first generation of American dressage riders.

On the National side, however, there is still some work to be done. There is sometimes a wide cleft between the amateur and the open division. At times when I judge, I wonder how trainers can send their students into the ring when the rider has little or no ability to guide the horse due to a severe lack of balance and stability in the saddle. This, of course, sets both horse and rider up for failure and at times borders on unintentional cruelty because the horse has to struggle to produce the movements required. If the rider has no sense of self perception and cannot see the “Big Picture,” it is up to the instructor to inform their student of his/her shortcomings and get to work to improve the situation.

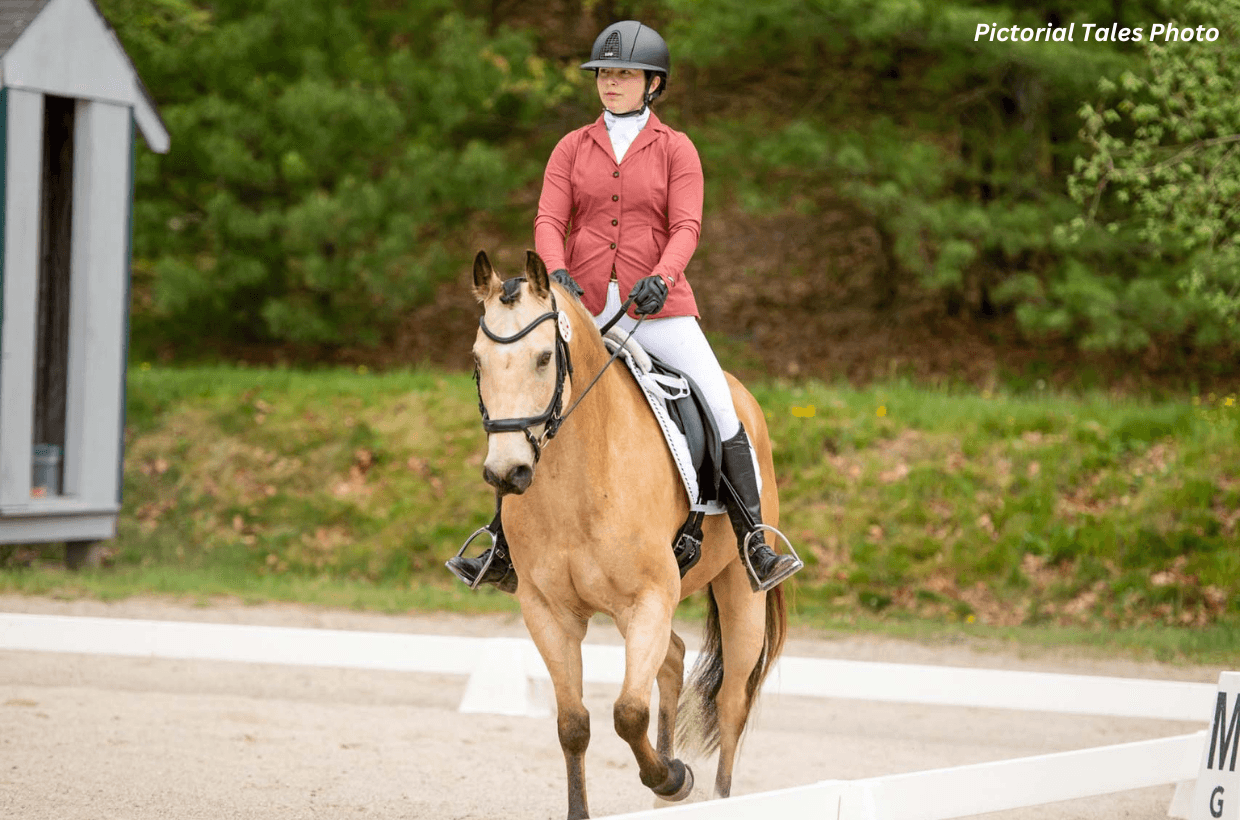

So, what are the main components of a “good seat?” First of all, riding is a matter of remaining within the center of gravity of the horse. This changes according to the gait and the task at hand, since the horse's balance is in a state of constant change. Few sports demand as much continuous education as riding, because of the many phases of learning. Horses change in the process of training and riders may ride several different horses. The learning never ends, often to the amazement of non-horsey friends and relatives who, twenty years later will exclaim, "Why are you still taking lessons?"

Some riders have an instinctive technique; quickness and sensitivity which set them apart, the rest of us have to keep plugging at it. Balance is the number one task, and it is best learned on the lunge line, with the horse on side reins and controlled by the instructor so the rider can focus on their seat without having to work on the horse's issues. The ideal seat is placed on the vertical, with the leg placed directly under the seat, the spine should be straight but relaxed, the rider’s weight placed equally over each seat bone, which is sitting at the same distance away from the spine of the horse. The rider's head is an important part, since it weighs a lot. The head should be carried on top of the spine to prevent the rider from falling forward over the withers of the horse and the shoulders from collapsing the chest. There are multiple exercises to be done on the lunge once the rider is comfortable, but in the beginning just finding that sweet spot of sitting “in" the horse rather than on top of him is the mission. The rider may at first balk at having to ride without stirrups, but they will soon discover that it is easier than working with them in the search for a deep and secure seat. In the beginning, the rider should hold on to the pommel or a strap to stay secure, but later they will let go and ride without the support of the hands. When comfortable at all gaits, it is time for transitions, which are the real “crunchers" on the lunge line. The teacher may suggest additional exercises to further develop ease in following the motion of the horse while remaining within the center of gravity. Once the mission is accomplished, it is time to pick up the reins and start taking charge of the horse.

Stability and balance are closely related, and once the rider is off the lunge, the instructor can view the position of the rider from the front and back as well as the side. Not uncommonly, you can then see the rider sliding further down one side of the horse than the other or collapsing in the waist on one side. This, of course, complicates the performance of the horse and makes it easier for the centrifugal force to pull the rider to the outside of turns and circles. Adding weights to your ankles can point out this lack of symmetry in the seat and will make the rider more aware of how to correct their position.

A few helpful hints to consider: Look straight ahead! This turns on your automatic balancing system, just as if you were walking on a balance bar, and helps to straighten your spine and move your shoulders back. When practicing, it is sometimes helpful to close your eyes at the walk, and sense the difference when your eyes are not guiding your posture. Keep your foot stable in the stirrup by putting the weight toward to inside of the stirrup iron in the direction of your big toe. This will help the rider’s lower leg to stay in touch with the horse. Check through stretching exercises if one of your hips is less supple than the other, which causes the horse to compensate on your “stiff side.” Perhaps it is not only the horse that is tight to the left?

Other than yoga and stretching off the horse, you can exercise your balance system on the horse over cavaletti and small jumps which also softens the rider’s knees and spine to easier absorb the impact of the movement under your seat. I often find it easier to work with riders with jumping background because they are not afraid of going forward and have a better instinct in following the horse's motion.

Once the basic balancing issues are taken care of, we have the challenge of becoming truly supple on the horse, i.e. able to allow the horse to move us without stiffening our bodies. The three components of elasticity, balance and stability are required to make the rider communicate better with the horse.

Next comes the task of becoming effective in the saddle in order to be able to give clear directions to the horse. For this the rider needs coordination, timing, a strong core and sympathetic hands. All this is impossible on a horse which is not on the bit and does not allow the rider to sit comfortably on its back. Therefore, it is better to allow the rider to use a martingale, chambon, or side reins on the schoolmaster until they learn to get and keep the horse round. Here come the hours on various horses on 20 meter circles until the muscles start to absorb and “remember" the movement of the horse. As this muscle memory improves, the rider no longer has to "decide" what to do every time he/she gives the horse an aid. The reactions to the horse become instinctive, and it feels almost as if you are riding with your spine, not with your head. This is what we call "feel" in absence of a more descriptive word. It is easy to detect, even after a few minutes whether a new student has a high potential to develop "feel" or not, just as one can immediately see talent in a young horse. But even the most talented rider has to work on improving core strength, coordination and technique in riding the movements as well as have a certain amount of courage when it comes to starting and training a young horse.

Riders with good technique can be recognized by their relaxed but focused attitude in the saddle. They have a pattern they work by, and they stick to it. They are completely coordinated with the horse and handle potential problems by actually forestalling them. They make the difficult movements look fluid and easy. These days, with the heightened sophistication in the sport, everyone can produce the movements. What impresses and wins in the end is the performance when the rider makes it all look easy!

About Anne: Anne Gribbons is an FEI 5* judge, USEF "S" and "R" Sports Horse Breeding judge. She has participated at numerous CDI's world wide, selection trials for Olympics and World Games, two FEI World Cup Finals and the 2009 European Championships in Windsor. She competed and trained extensively in Europe, rode in ten USET Championships and was a member of the U.S. silver medal team at the 1995 Pan American Games in Argentina. Anne has served as the United States Technical Advisor/Coach for Dressage from 2010 through the 2012 Olympics and was a member of the FEI Dressage Committee from 2010 through 2013.